GO-SHIP P14N: Wrapping up

P14N Log: Wrapping up the expedition

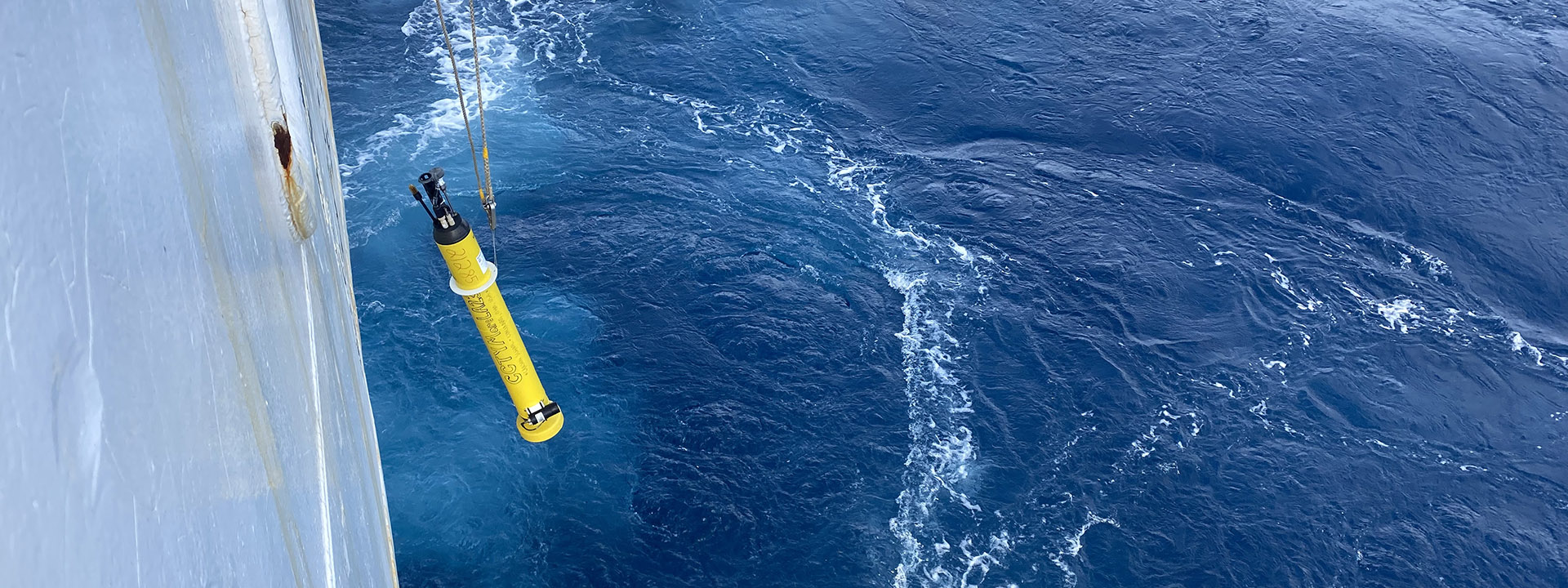

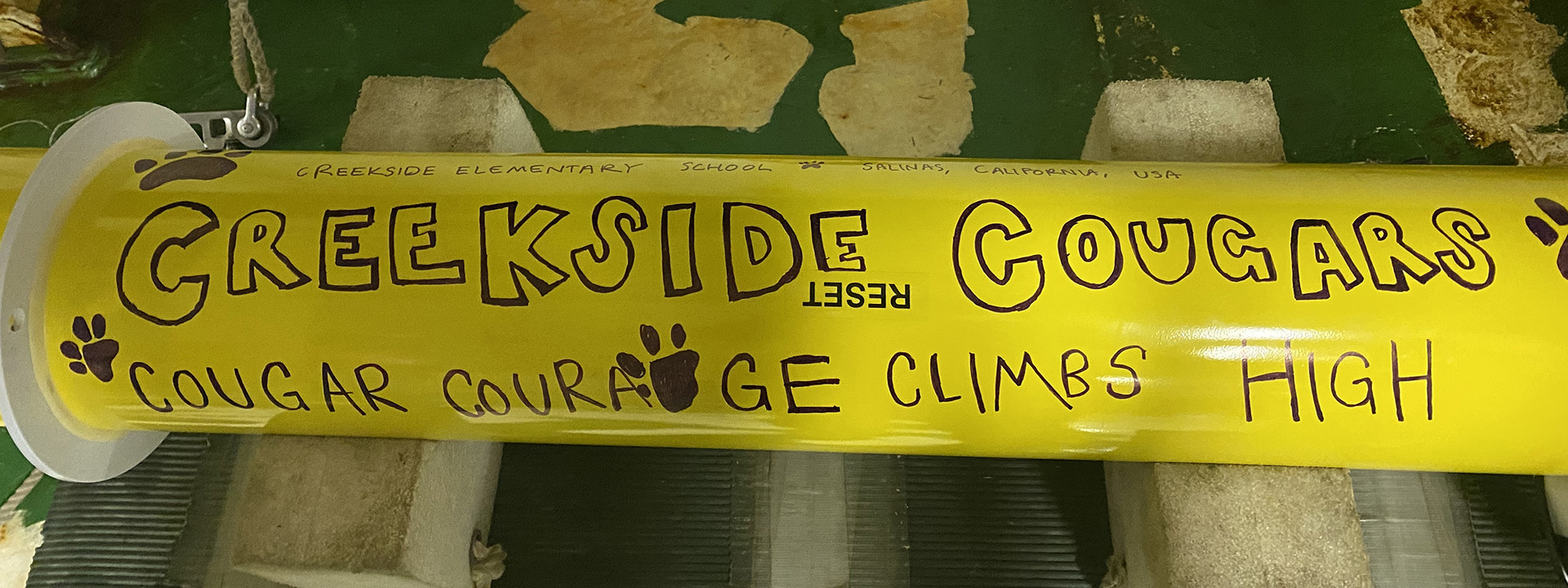

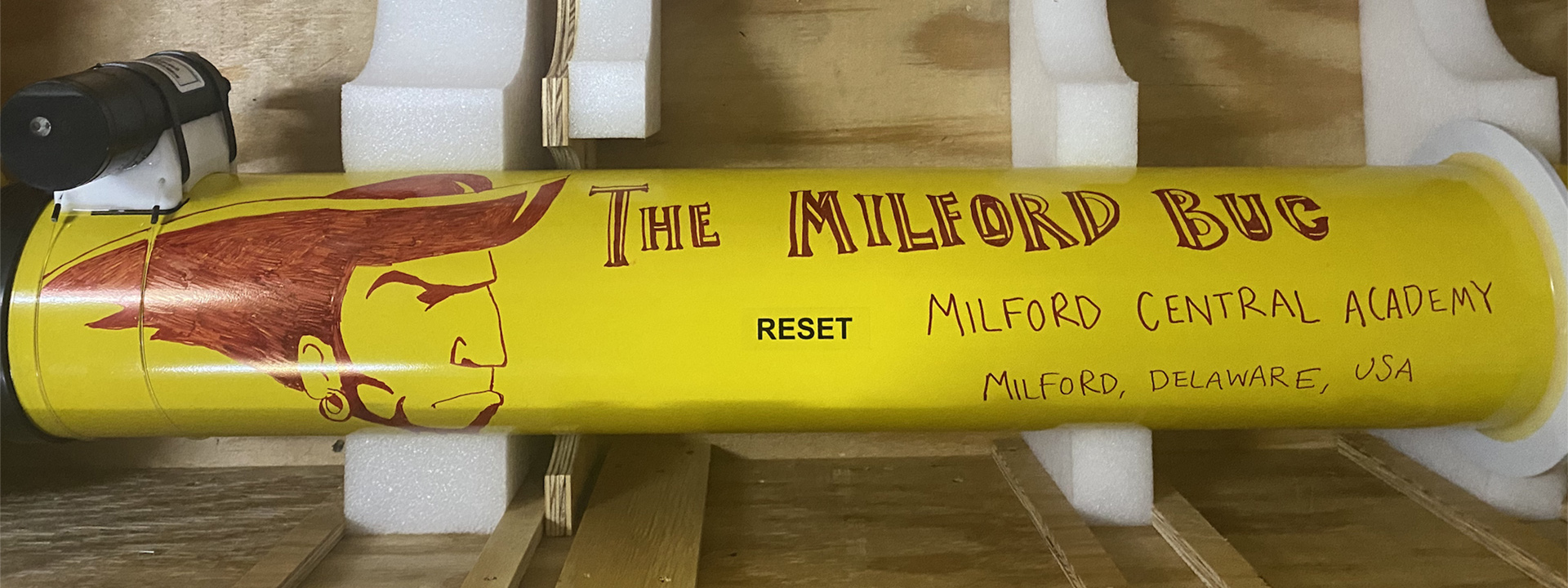

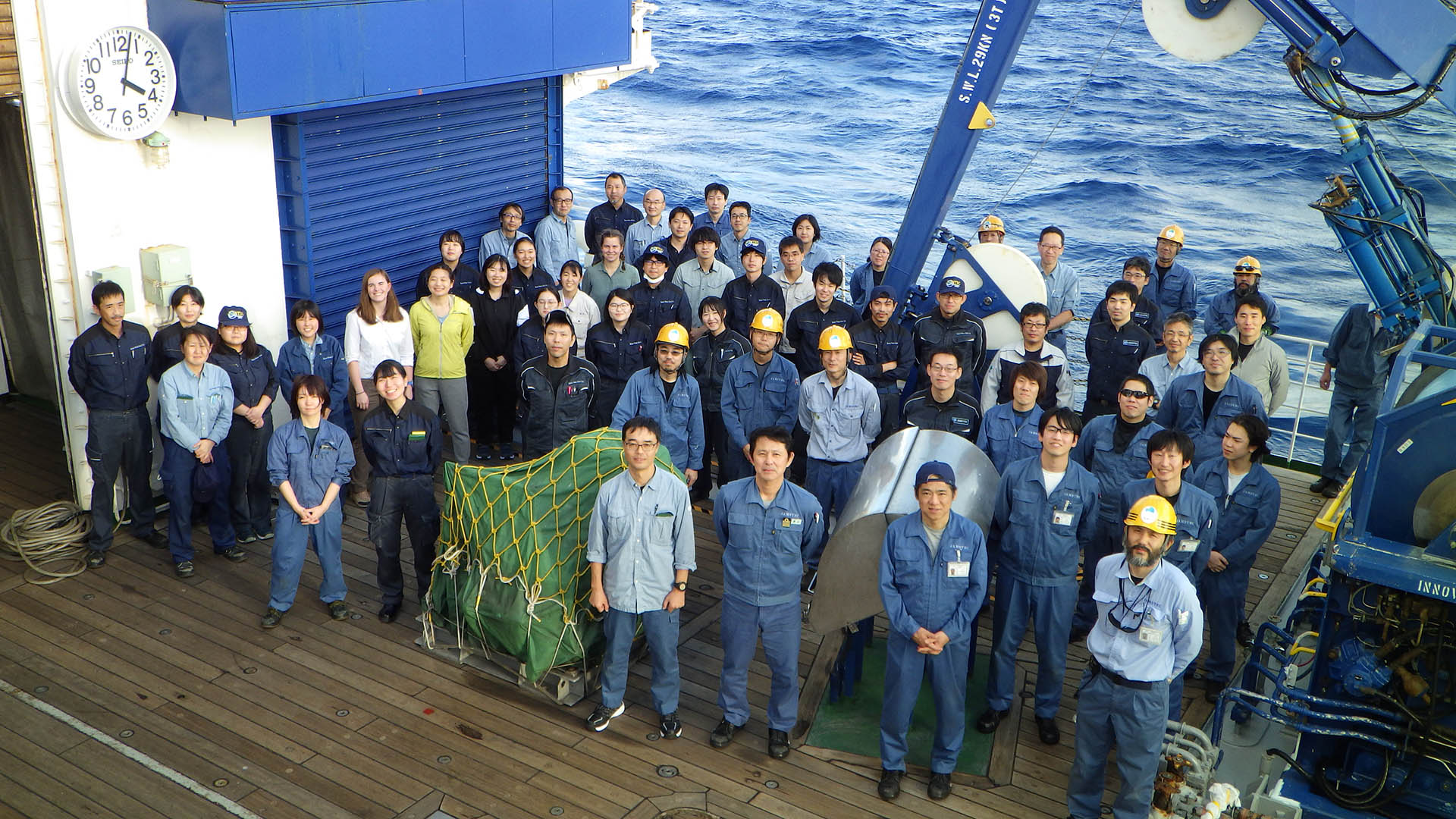

All of the sampling stations on P14N have been completed, and the last three floats are out collecting data! For our final few days, all that is left for scientists to do is pack up laboratories, write up cruise reports, and return to a regular sleep schedule.

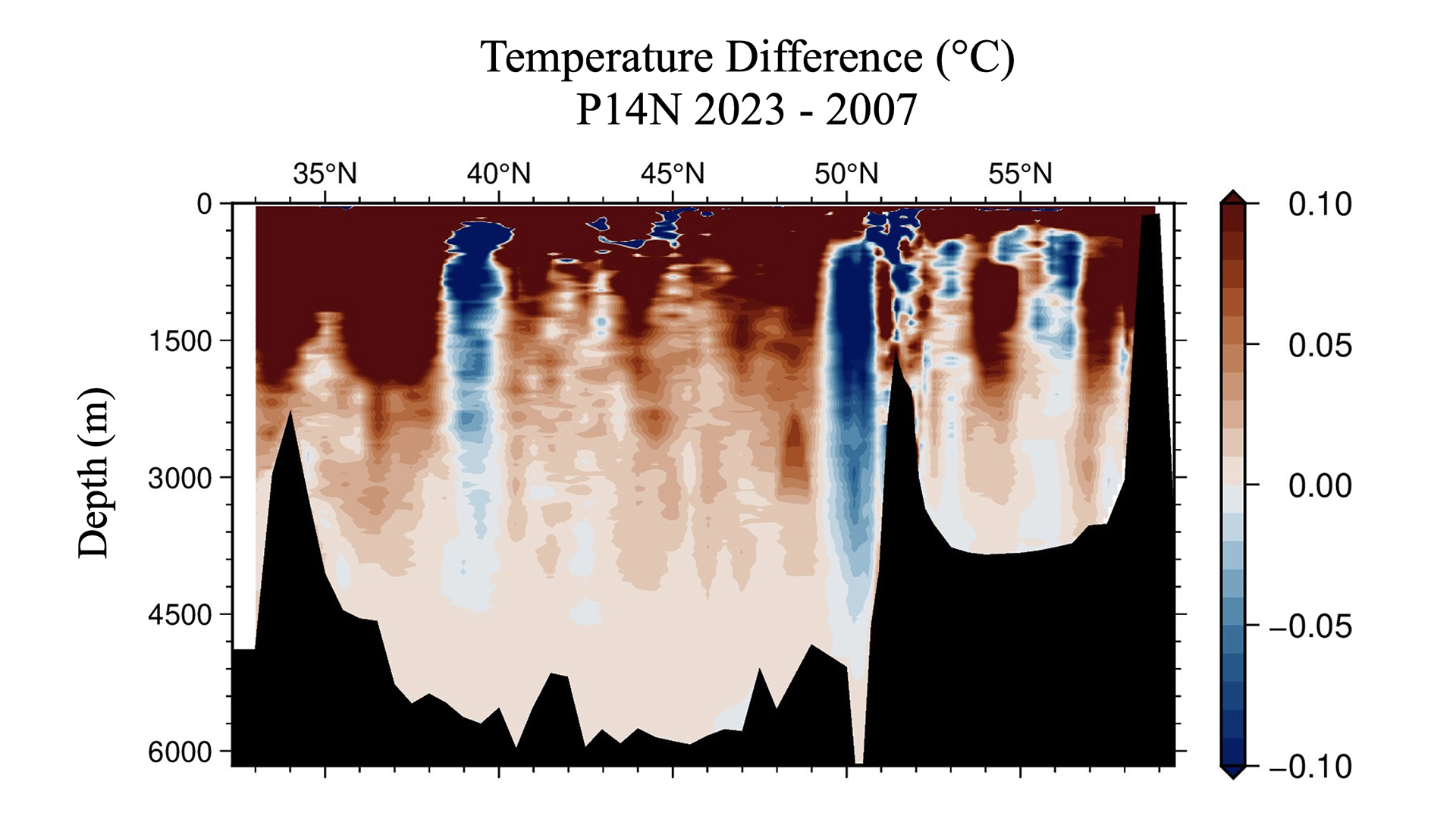

Some preliminary data from the cruise has already been drawn up. The figure below shows the difference in temperature since oceanographic line P14N was last observed, in 2007. The only thing scarier than this figure is imagining what the Earth would be like if the ocean wasn’t absorbing so much heat! The chief scientist, Dr. Katsuro Katsumata, says that the patches where 2023 is colder might be related to eddies or to meridional displacement of ocean currents.

It has been a truly unique time for me aboard the Mirai. Of course, since it is a Japanese research cruise, many things have been different from what I’m used to on American ships, or in general. There are certain rooms where street shoes are not allowed, including the gym and a Japanese-style lounge room with tatami floor mats, and chairs and tables that put you at floor level. Several rooms are designated for smoking. Employees of JAMSTEC and Marine Works Japan wear uniforms, and collared shirts are required in the dining hall. Curtains cover many doorways, which is very nice so you can keep your door latched open but still have privacy. The seated showers are relaxing, not to mention way safer than sliding around a wet tile floor on a moving ship.

My favorite difference is probably the way that sampling is done. On American research cruises I have been on, each scientist collects only their own samples. So, one scientist might collect carbon dioxide samples, and another only collect chlorophyll, and so on, and they move around the sampling rosette, sampling each Niskin. On JAMSTEC cruises, instead, all sample bottles for each Niskin are organized into baskets, and then you pick a basket, and collect all of the samples that are needed from that Niskin. Everyone stays and helps until all of the sampling is finished and the samples have been delivered to the laboratories for analysis. I found this sampling system efficient because you don’t have to wait for others to be finished with a Niskin, and there is less awkward shuffling around the rosette. It felt nice to work as a team to get everything done, instead of “every scientist for themselves.”

I was also impressed by how, after sampling, every bottle was dunked in freshwater and dried before being sorted into their bins, and the sample baskets and other items were also rinsed with freshwater. This is a simple step that I haven’t seen as a regular practice before. I appreciate that it keeps laboratories clean, and it allows items to last longer before they have an irreversible buildup of sea grime. I observed people taking similarly good care of their personal items. My camping tent is glad that I am taking note.

Unfortunately, the GO-BGC shipment of sampling supplies to Dutch Harbor did not arrive in time for departure. So, I couldn’t fulfill my main purpose for being onboard, to collect samples for sensor validation measurements. Luckily, it made no difference to the scientists at sea, since I could still help daily with preparing the CTD, putting together sampling baskets, doing bucket sampling (yep, collecting surface seawater by hauling up a 5-gallon bucket) and sampling the CTD. A ton of parameters were measured at every station, so sampling the 36-bottle CTD takes several hours. Under Japanese law, employees can work a maximum of 8 hours per day, so extra hands are helpful to get everything done.

I feel lucky to have had such a fun and interesting experience. I’m happy to have contributed to these high-quality decadal ocean measurements and to the seven floats out collecting data. I am very grateful to GO-BGC for the opportunity to participate, and to everyone on board the Mirai for welcoming me.