Navigating the Ice

Ship Encounters with Icebergs

DATE: 3/22/2024

As the R/V Marcus G. Langseth sailed toward 48 degrees South on March 14th, 2024, we were unexpectedly greeted by a trio of small icebergs, barely visible through the morning fog. A crew member remarked on the rarity of such a sight, igniting a surge of excitement among us scientists.

Icebergs had always been a dream sight for me, tucked away on my bucket list for years. Yet, here we were, amid the icy waters of Antarctica, with the opportunity to witness them firsthand. Fueled by anticipation, I retrieved my camera, reserved for the most memorable occasions.

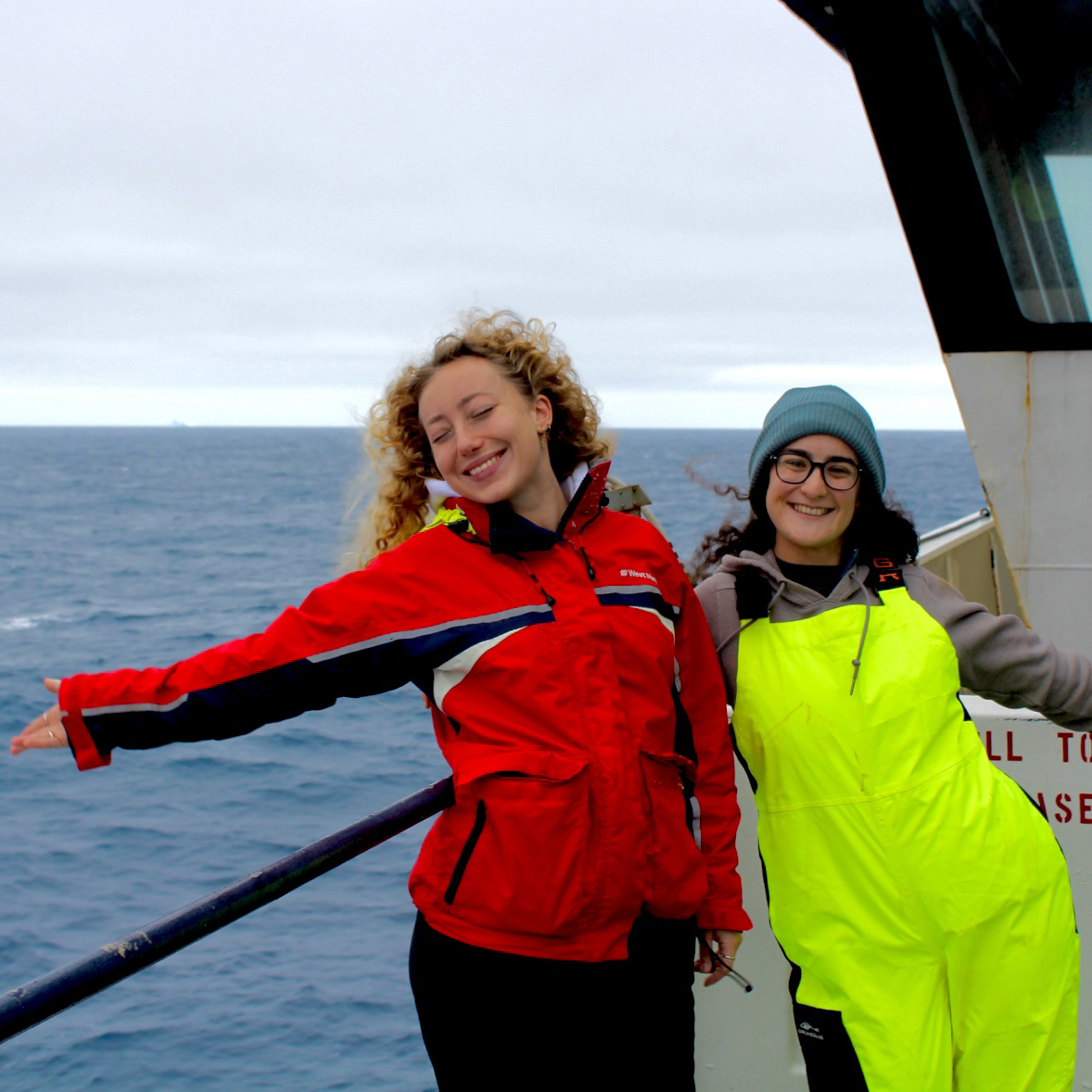

Ascending to the main deck alongside fellow science team members, we eagerly prepared to capture the moment. However, to our delight, the scene unfolded even greater than expected – larger icebergs loomed on the port side, their striking forms emerging from the mist. One of the first icebergs the Langseth encountered, roughly two miles away from the vessel, is pictured above.

Clara Gramazio and Rachael Cohn (UMiami) enjoying the view of the icebergs.

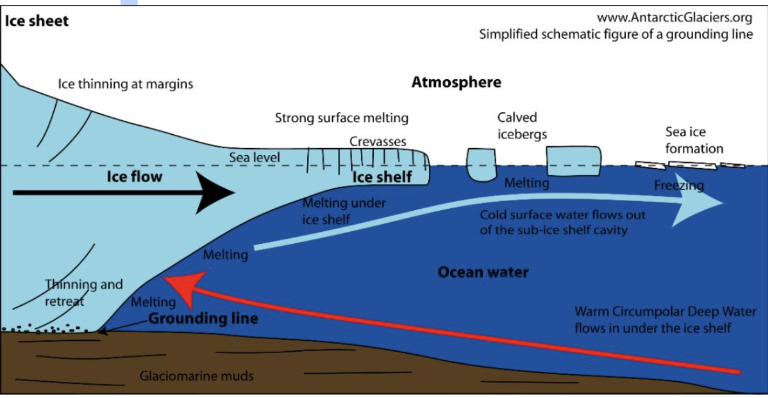

Icebergs originating from Antarctica are the giants of the Southern Ocean, born from the continent’s vast ice sheets. Formed through a process that takes thousands of years, these icebergs begin their journey as snowfall accumulates on the Antarctic landmass, gradually compacting under the immense weight of subsequent layers. Over time, this compressed snow transforms into ice, forming colossal glaciers that inch their way toward the ocean’s edge.

As these glaciers reach the coastline, they encounter the relentless forces of nature: the warming temperatures, the erosive power of waves, and the sheer gravitational pull. Under these pressures, immense chunks of ice break off from the glaciers, creating icebergs of various shapes and sizes. Some are small and irregular, while others can rival the size of cities, their towering forms dwarfing everything in their vicinity.

A diagram showing how an iceberg is formed. https://resources.arctickingdom.com/the-cycle-of-an-iceberg-from-glacier-to-the-ocean.

The process of iceberg formation, known as calving, is a dynamic interplay between the Antarctic ice and its surrounding environment. Climate factors, ocean currents, and even the topography of the seabed, all play crucial roles in determining where and how icebergs are born. Once set adrift, these icebergs become part of the Antarctic’s frozen diaspora, navigating the treacherous waters of the Southern Ocean, a stark reminder of the continent’s glacial legacy and the profound impact of climate change on Earth’s icy realms.

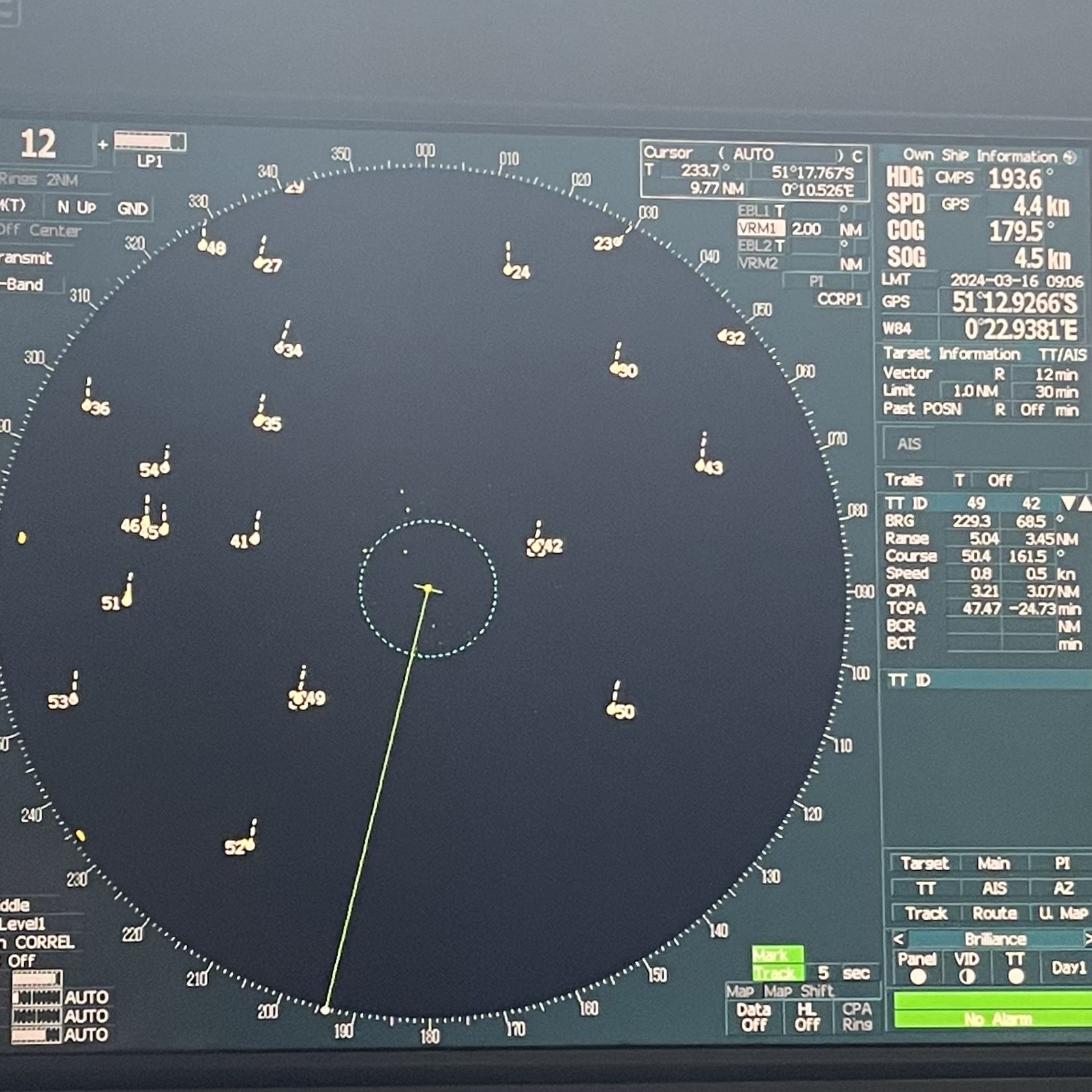

To detect icebergs, the R/V Marcus G. Langseth uses the JRC (Japan Radio Company) 3-centimeter radar system (among other technologies) equipped with specialized capabilities for detecting icebergs in maritime environments. This iceberg detection feature utilizes the radar’s high-resolution imaging, long-range detection, weather detection, and real-time monitoring capabilities to identify ice masses floating in the ocean, thereby helping vessels navigate safely through icy waters.

The JRC onboard the R/V Marcus G. Langseth showing nearby icebergs. Picture by Zachary Erickson (NOAA PMEL).

Large iceberg viewed off the starboard side of the ship during sampling.

Discovering icebergs this far south reveals a stark reality: ice from Antarctica is drifting farther north, hinting at increased melting due to rising global temperatures. This contributes to sea-level rise and signifies environmental shifts, highlighting the ongoing loss of polar ice.

Icebergs drifting to 48°S signal significant shifts in climate patterns. As global temperatures rise, polar ice sheets melt faster, leading to an increased number of icebergs breaking off and journeying southward. Climate change also alters ocean currents, guiding icebergs into regions they haven’t historically frequented. This movement can disrupt marine ecosystems, impacting temperatures, habitats, and the migration of marine life. Furthermore, the unexpected presence of icebergs in lower latitudes poses heightened risks to maritime navigation, prompting the need for closer monitoring and potential route adjustments to ensure safe passage.

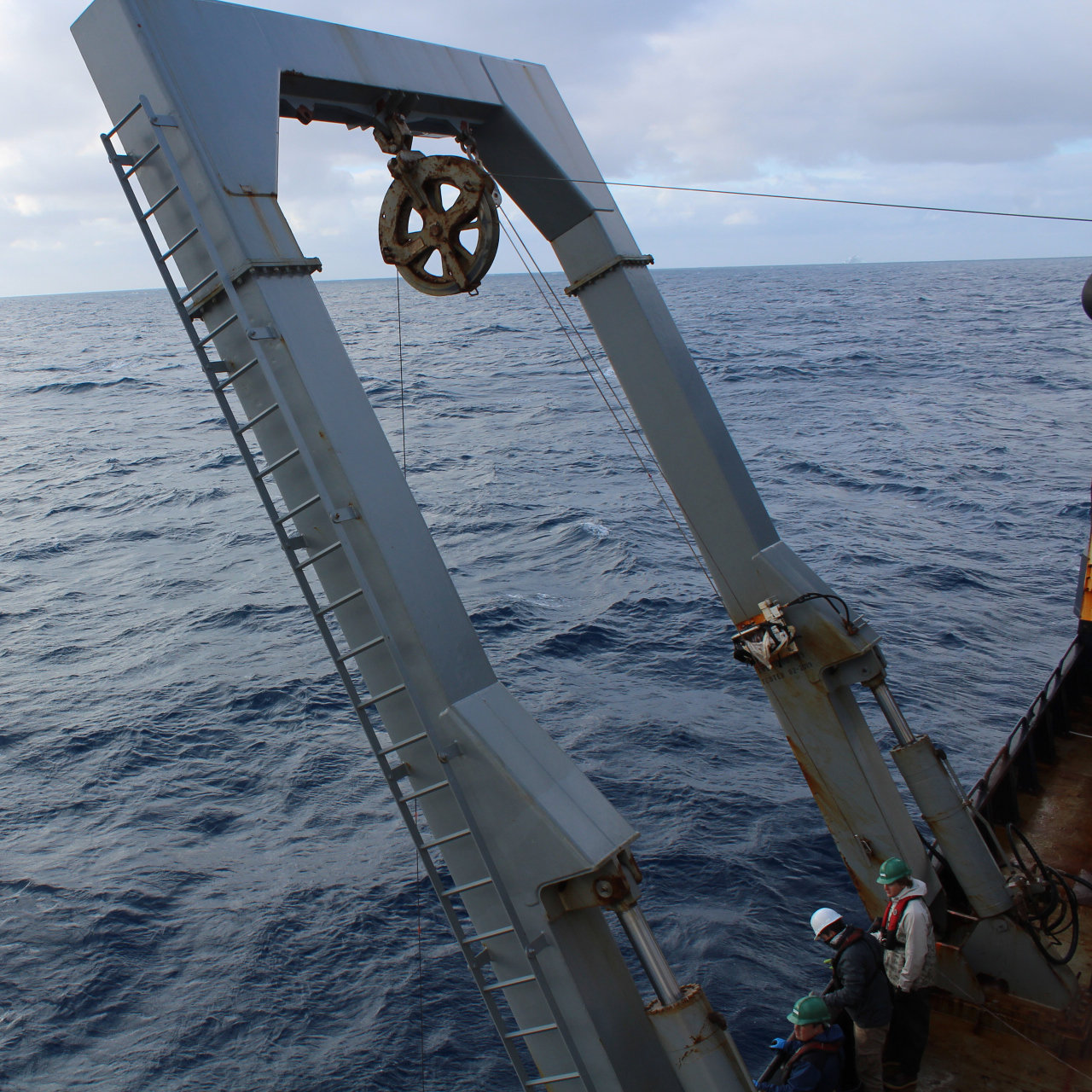

From left to right: Eric Wisegarver (NOAA PMEL), Christian Saiz (UM CIMAS), and Evan Jozsa (UW CICOES/NOAA PMEL), standing by to recover the CTD amidst Icebergs.

One of the last icebergs viewed by the Langseth, from the starboard side of the ship.

International organizations, such as the International Ice Patrol (IIP) and the International Ice Charting Working Group (IICWG), collaborate to monitor icebergs in the Southern Ocean. They employ a range of tools, including satellites, aircraft, autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs), and mathematical models.

Satellites offer continuous coverage, detecting and tracking icebergs over time. Aircraft conduct surveys, providing high-resolution images of iceberg size and distribution. Oceanographic instruments, such as buoys and AUVs, gather data on ocean conditions, aiding in understanding iceberg movement. Mathematical models simulate iceberg drift, predicting their future paths and assessing risks to maritime navigation. Through these efforts, organizations work together to ensure the safety and effective monitoring of icebergs in the Southern Ocean.

Max Pacatte, undergraduate student at the University of California – Santa Barbara, making measurements of dissolved organic carbon on this cruise.

To learn more about the day-to-day life onboard the R/V Marcus G. Langseth, follow the link to my personal blog.

All pictures by Max Pacatte unless otherwise noted.

Max Pacatte (UCSB) enjoying the view of Icebergs while sampling.